B'ix

Solapas principales

Hay muchas referencias al cultivo del maíz a lo largo del Popol Wuj. Cabe señalar que la labor agrícola se asocia en diversos momentos del texto con los personajes femeninos y masculinos. Tal labor se expresa con una forma verbal o nominal de la morfema b'ix (milpa, mata de milpa). El lingüista k'iche' Sam Colop (2008: 79n117 y 118) explica algunos elementos lingüísticos relacionados con el cultivo del maíz y la forma en la que se representa en el texto. Primero, comenta la relación entre la tradición oral y el vocabulario del maíz. Afirma: "Conforme al discurso k'iche', el narrador no sólo cuenta la historia como un hecho pasado sino 'ubica', 'transporta' al lector al lugar de los hechos. Éste se marca con el locativo chiri' 'aquí' en lugar de chila' 'allá,'" tal como se observa en varias invocaciones de la milpa. En la siguiente nota sobre la milpa, el investigador explica porqué los autores k'iche' usan la misma palabra para hablar de la milpa y la planta que se cultiva allí. Conforme a Colop (2008: 79n118), la "mata de milpa" se debe entender como "un terrón o grupo de 4 ó 5 plantas de maíz sembradas en un mismo hoyo. No una sola planta, como literalmente podría traducirse. Se siembra el maíze en grupos de 4 ó 5 granos de maíz, luego se limpia y 'calzan' las plantas para que no las bote el viento. Por eso, llegado el tiempo y cuandl la milpa está creciendo se pueden ver volcancitos de tierra al pie de las 4 ó 5 plantas a lo largo de los terrenos." Al principio del texto, Colop (2008: 24n13) clarifica que tal terreno se entiende en términos cosmológicos. Arguye que "las cuatro estacas" del mundo es "una metáfora que asocia el cosmos con un campo de siembra donde hay una estaca en cada una de las esquinas."

Throughout the Popol Wuj, various male and female characters are charged with cultivating maize, typically expressed with a verbal or nominal form of the root word b'ix (cornfield, corn plant). According to anthropologist Allen J. Christenson, the four-part significance of the physical design of the cornfield is directly related to broader Mayan and Mesoamerican understandings of the structure of the universe and humankind's relationship to the sacred. He writes: "The gods thus laid out the extent of their creation by measuring its boundaries, driving stakes to mark its four corners, and stretching a measuring cord between the stakes. Andrés Xiloj, a modern Quiché aj q’ij priest who worked with Tedlock on his translation of the Popol Vuh, recognized the terminology of this passage and explained that the gods were measuring out the sky and earth as if it were a maizefield being laid out for cultivation (D. Tedlock 1996, 220). Vogt quoted a Tzotzil-Maya from Zinacantán as saying that the universe is “like a house, like a table,” representing that which is systematic, and well-ordered (Vogt 1993, 11). Wisdom also recorded that the Chortí-Maya of Guatemala considered both the squared maize field and the shamanic altars on which traditionalist Maya priests conduct their divination rituals to be the world in miniature (Wisdom 1940, 430). By laying out the maize field, or setting up a ritual table, the Maya transform secular models into sacred space. With regard to the maize field, this charges the ground with the power of creation to bear new life. In a similar way, the divinatory table provides a stage on which sacred geography may be initimately studied, and even altered. Note that on pp. 81-82 (lines 565-623) the creator deities carry out a divinatory ceremony in an attempt to create the first human beings. A prominent Quiché aj q’ij priest, named Don Vicente de León Abac, described his work to me in this way: 'When I am seated at my table, I am aj nawal mesa [of, or pertaining to, the spirit essence of the table]. My body is in the form of a cross just like the four sides of the world. This is why I face to the east and behind me is the west. My left arm extends out toward the north, and my right arm points to the south. My heart is the center of myself just as the arms of the cross come together to form its heart. My head extends upward above the horizon so that I can see far away. Because I am seated this way I can speak to Mundo [World]'" (2007: 65n39).

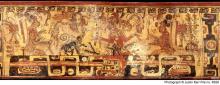

Image credit: Justin Kerr, Maya Vase Database #K626, Dressing of the Maize God after his resurrection.