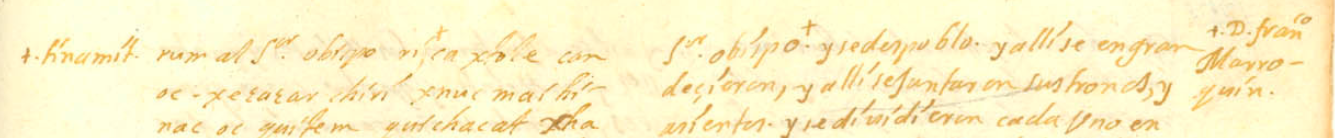

Señor obispo (Francisco Marroquín)

Solapas principales

The legacy of Francisco Marroquín, founder and first bishop of the Archdiocese of Guatemala, would have been familiar to Ximénez and his contemporaries. Having accompanied Fray Juan de Zumárraga and “los letrados que [iban] a constituir la nueva audiencia” to Mexico in 1529 (Saenz 16), Marroquín arrives to Guatemala in 1530 to begin his service as parish priest, a position offered to him by Governor Pedro de Alvarado (Ibid., 19). Drawing from the chronicles of Dominican historian Antonio de Remesal, Karl Scherzer notes the following in his 1857 edition of the Popol Wuj:

"Marroquín hizo construir en la vecindad de la antigua capital en el pueblo de San Juan del Obispo un palacio magnífico por las manos de los prisioneros de guerra, que los conquistadores hicieron esclavos. Este edificio continúa hasta hoy llamándose palacio de los esclavos" (122).

Marroquín was witness to the catastrophic earthquake that destroyed the capital, Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala; and which claimed the life of Alvarado’s widow Beatriz de la Cueva, a few days after she was named Governor of Guatemala. Recalling the scene in vivid detail in Chapter CCXXIII of Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who had lived alongside Marroquín for more than twenty years (Saenz 7), notes that he owes his account of the events to the bishop: “porque entre los papeles y memorias que dexó el buen Obispo Don Francisco Marroquin, estaban escritos los temblores, cómo y quando, y de qué manera pasó, según aquí va declarado.”

As J.T. Medina notes in the introduction to his 1905 edition of Marroquín’s Doctrina cristiana en lengua guatemalteca, in addition to overseeing the construction of the parish cathedral, the bishop also “logró que se fundase una cátedra de gramática y erigió un hospital; hizo que fueran frailes de San Francisco y la Merced y quiso llevar también a los jesuitas” (n.p.) Additional projects that Marroquín had hoped to develop included a convent, a school for orphaned girls, and a University (ibid). Marroquín’s bilingual Spanish and Cakchiquel edition of the Doctrina cristiana was first printed in Mexico in 1556, roughly one hundred and fifty years prior to Ximénez’s transcription of the Popol Wuj (ibid, n.p.).

Although the relationship between Marroquín and Fray Bartolomé de las Casas would eventually prove to be rivalrous and rocky, the two were united, if only nominally, in their aversion to the enslavement and mistreatment of indigenous populations. In a letter addressed to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1537, Marroquín notes that he left instructions “para que conforme a ella, hiciese la tasación..a quien quedó poder de mi iglesia y de la protección, que es un fray Bartolomé de las Casas, gran religioso y de mucho espíritu; y he sabido que ansí se hacía como yo lo dexé ordenado” (Saenz 26).

As Saenz de Santa María points out, “Marroquín creía urgente una revisión total de los tributos que los indios pagaban. Había que tasarlos, y para ello había que recorrer el país de punta a cabo y examinar en cada caso las posibilidades de cada grupo indígena,” an ambitious mission that was well underway at the time of the bishop’s correspondence with Charles V (25). One such trip would later be recorded by the K’iche’ authors of the Popol Wuj, and again with more specificity by Francisco Ximénez.

In addition to these literary footprints, Marroquín, and missionaries like him, left an important mark upon the physical and built environment of colonial Mesoamerica.